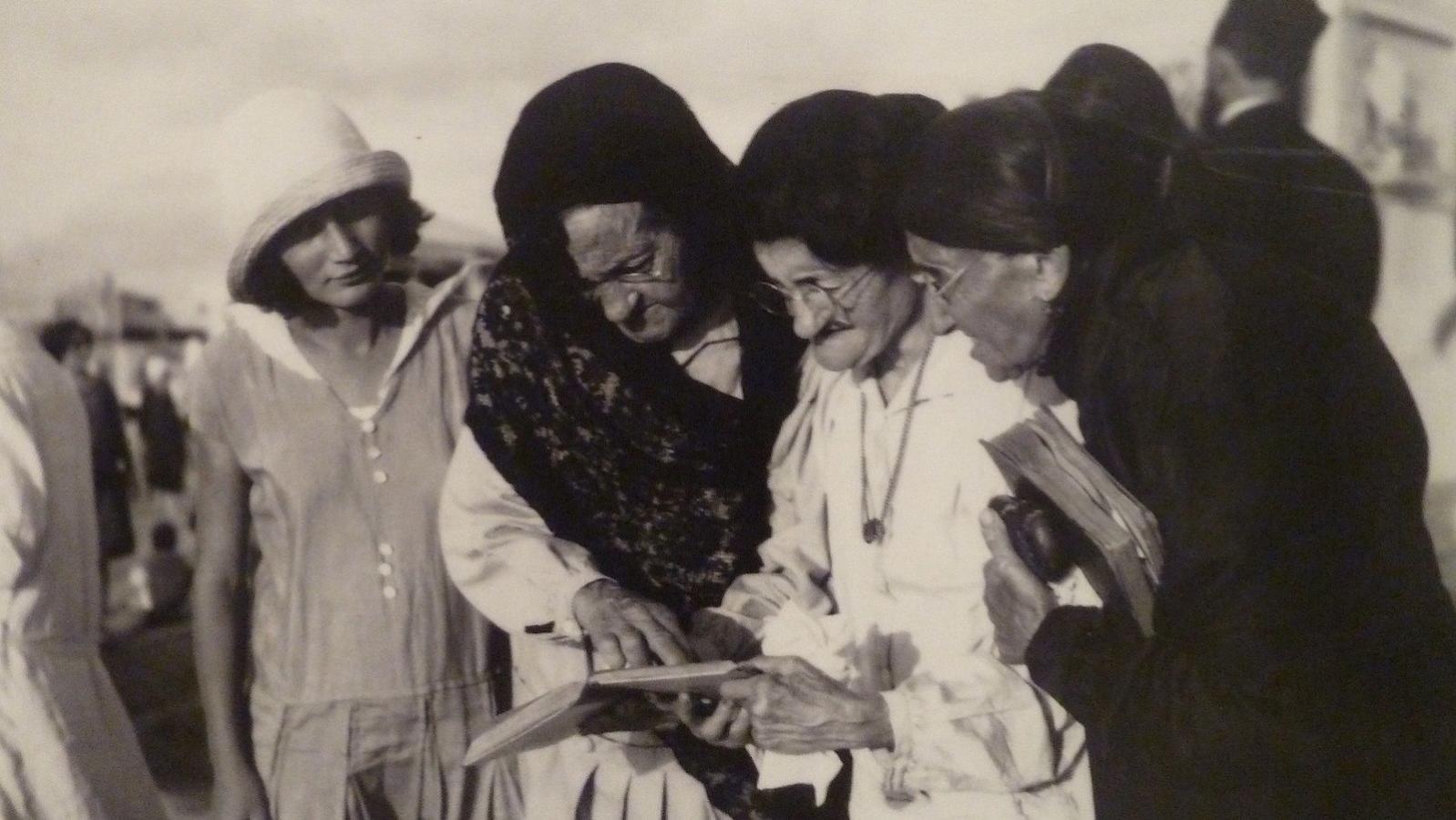

On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, Jews traditionally proceed to a body of running water, preferably one containing fish, and symbolically cast off their sins. The Tashlich ceremony includes reading the source passage for the practice, the last verses from the prophet Micah (7:19), “He will take us back in love; He will cover up our iniquities. You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea.”

Selections from Psalms, particularly Psalm 118 and Psalm 130, along with supplications and a kabbalistic prayer hoping God will treat Israel with mercy, are parts of Tashlich in various communities.

History of Tashlich

The custom developed around the 13th century and became widespread despite objections from rabbis who feared superstitious people would believe that tashlich, rather than the concerted effort of teshuvah, had the power to change their lives. Religious leaders were particularly opposed to the practice of tossing bread crumbs, representing sins, into the water, and even shaking one’s garments to loosen any evil clinging to them was discouraged.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

See the full text of the Tashlich prayer here.

Superstitious rites most likely did influence ceremony. Primitive people believed that the best way to win favor from evil spirits living in waterways was to give them gifts. Some peoples, including the Babylonian Jews, sent “sin‑filled” containers out into the water. (The Talmud describes the practice of growing beans or peas for two or three weeks prior to the new year in a woven basket for each child in a family. In an early variation of the Yom Kippur kaparot ritual, the basket, representing the child, was swung around the head seven times and then flung into the water.) Kurdistani Jews threw themselves into the water and swam around to be cleansed of their sins.

The Symbolism of Water

To make the practice symbolic rather than superstitious, the rabbis gave it ethical meaning. Through Midrash, they connected the water with the Akedah, the binding of Isaac. When Abraham was on his way to sacrifice Isaac, they said, Satan (which could be understood as the voice inside Abraham telling him not to kill his beloved son) tried to stop him. When Abraham refused to heed his voice, Satan became a raging river blocking Abraham’s way. Abraham proceeded nevertheless. When the water reached his neck and he called out for God’s help, the waters immediately subsided.

Water was also seen as symbolic of the creation of the world and of all life. Kings of Israel were crowned near springs, suggesting continuity, like the King of Kings’ unending sovereignty. Since the prophets Ezekiel and Daniel each received revelation near a body of water, it was seen as a place to find God’s presence. As the element of purification, water also represents the opportunity to cleanse the body and soul and take a new course in our lives. (Later rabbis continued to protest against the ritual, on grounds that it encouraged new sins by creating a social situation where people could gossip and men and women mingle, as Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story “Tashlich” illustrates.)

Although the rabbis preferred that Tashlich be done at a body of water containing fish (man cannot escape God’s judgment any more than fish can escape being caught in a net; we are just as likely to be ensnared and trapped at any moment as is a fish), since this is, after all, a symbolic ceremony, any body of water will do, even water running out of a hose or a faucet.

If the first day of Rosh Hashanah falls on Shabbat, Ashkenazi Jews [Jews of European descent] do Tashlich on the second day (so as not to carry prayer books to the water, which would violate Sabbath laws). Sephardic Jews [Jews of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern descent] perform the ritual even on the Sabbath [as do a number of liberal Jews]. The ceremony can take place any time during the holiday season through Hoshanah Rabbah at the end of Sukkot.

Excerpted from Celebrate!: The Complete Jewish Holidays Handbook, reprinted with permission of the publisher. Copyright 1994 by Jason Aronson Inc.

Want to learn more about the High Holidays? Sign up for a special High Holiday prep email series.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.

Tashlich

Pronounced: TAHSH-likh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, literally “cast away,” tashlich is a ceremony observed on the afternoon of the first day of Rosh Hashanah, in which sins are symbolically cast away into a natural body of water. The term and custom are derived from a verse in the Book of Micah (7:19).

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.