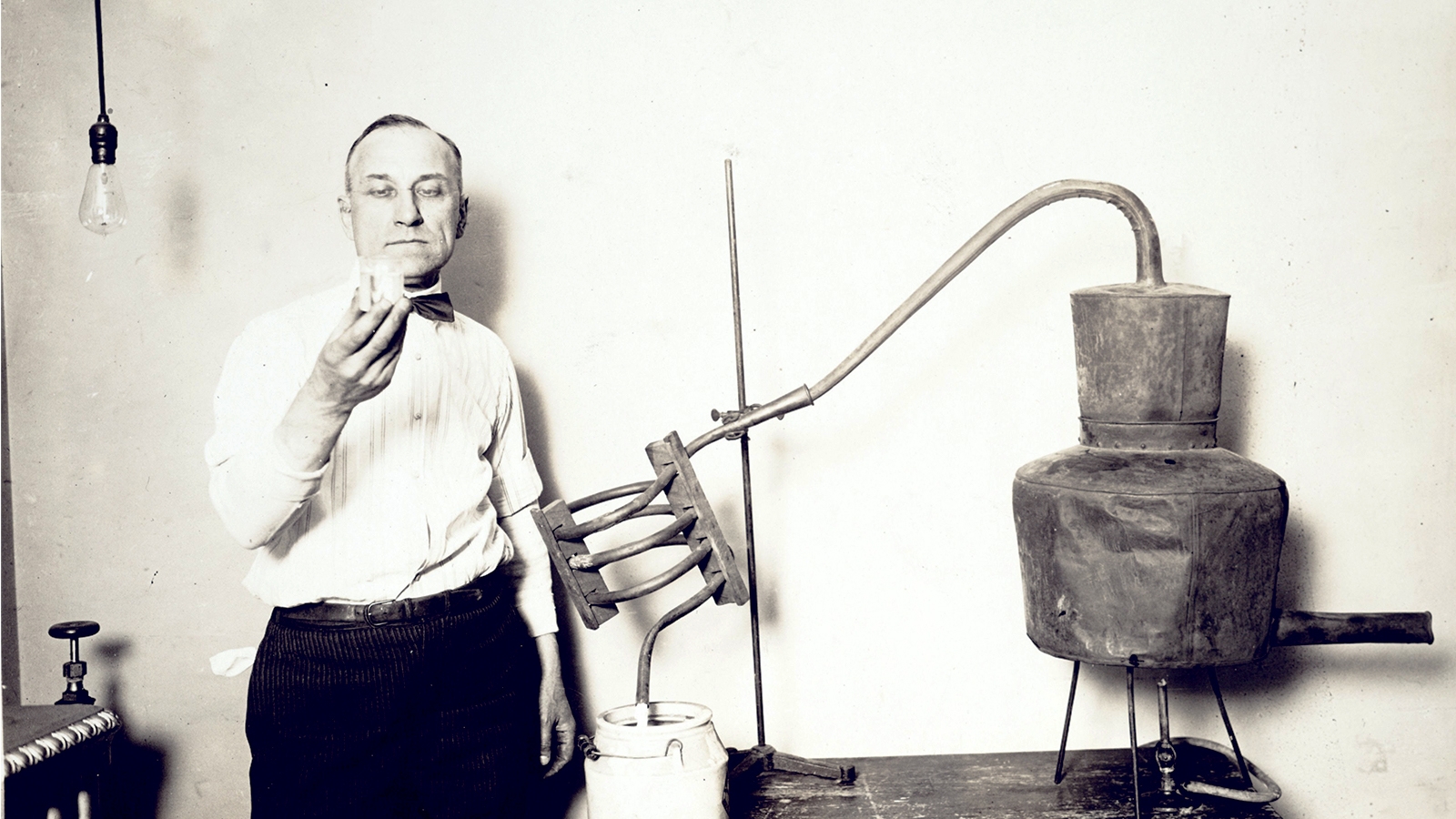

You likely know about Prohibition, the ban of alcohol in the United States that lasted from 1920 to 1933 and shuffled in the Roaring Twenties. But did you know how involved Jews were in bootlegging — the illegal selling and making of alcohol?

Bootlegging was a lucrative business that opened the door to a desired underground social scene. So, for many Americans, it was glamorized rather than marginalized. The leaders of the industry, the “gangster class,” were predominantly Jewish; in “Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition,” author Marni Davis says that 50% were Jewish, 25% Italian and around 10% were Irish. Many American Jews were drawn to the illegal alcohol business because it helped them to acculturate, allowing the most prominent Jewish bootleggers to reach the upper echelons of society.

Alcohol and Judaism

Alcohol has always played an important role in Jewish life. Wine (or grape juice), particularly, is paramount to keeping Jewish tradition alive. On Passover, for instance, four cups of wine are consumed. The Torah commands Jews to “remember the Sabbath day” and observe it. Kiddush, the blessing over wine, is how Jews remember the Sabbath. Medieval philosopher Maimonides explained the practice is a way of creating a sense-memory.

Despite the religious obligation to drink wine on a weekly basis, Jews were known as being stereotypically sober people. In Glynn Dynner’s article ‘‘A Jewish Drunk Is Hard to Find’: Jewish Drinking Practices and the Sobriety Stereotype in Eastern Europe,” she quotes a Polish nobleman who said, “The Jews are always sober, and this virtue should be conceded: drunks are rare among Jews.’’ This belief was widely shared by Polish landowners who in turn, exclusively leased taverns and distilleries to Jews. According to Dynner in her other work, “Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, and Life in the Kingdom of Poland”, by the mid-19th century, 85% of all Polish taverns had Jewish management and between 30 and 40% of all Polish Jews worked in the alcohol industry. For most Polish Jews, alcohol was their livelihood.

The Nosher celebrates the traditions and recipes that have brought Jews together for centuries. Donate today to keep The Nosher's stories and recipes accessible to all.

Jews who kept a kosher diet, which forbade drinking wine that was produced or even distributed by non-Jews, felt it necessary to be involved in the alcohol industry. This restriction created a profitable opportunity for the entire community. If Jews were to drink wine, a religious requirement, they had to be a part of every facet of its creation from harvesting the grapes to handling the shipments.

Jewish Immigrants and the U.S. Alcohol Industry

For many American Jews, the alcohol trade from distilling to distributing was a skill they brought from the Old Country. In America, they found it was easier to enter the whiskey industry rather than the beer industry, which was controlled by the Germans. The beer industry was also vertically integrated; the Germans only hired fellow Germans. In contrast, the whiskey industry didn’t even have a direct distribution system, which enticed Jewish entrepreneurs. Plus, unlike wine and beer, which had strong associations with the Old World, whiskey was characterized as an American drink. Not only did it serve as an avenue to economic success, it also manifested a feeling of patriotism; American Jews were contributing to the fabric of American culture.

When new Jewish immigrants would arrive, the existing community offered them work in the whiskey industry. Before long, Jews managed all elements of the trade. According to Davis, “By 1900, Jews made up 25 percent of the whiskey distillers, rectifiers, and wholesalers in Louisville, a city where the Jewish population was about 3 percent of the municipal whole.”

Many Jews immigrated to America to escape persecution, but Prohibition threatened their economic mobility and social stability. The Temperance Movement, a largely Protestant campaign, believed that alcohol was a sin that was only cured with abstinence. This challenged Jewish culture because asceticism was never a part of the Jewish way of life. The Temperance Movement also threatened the Jew’s feeling of religious freedom. The movement, which garnered the support of the Ku Klux Klan, wanted to embed their Protestant religious dogma and xenophobic beliefs into the social order. To the movement’s success, their efforts led the federal government to enact the Volstead Act in 1919, paving the way for Prohibition.

However, despite the Temperance Movement’s best efforts, the First Amendment, which protects religious freedom, provided loopholes to acquiring alcohol. Not only did Jews have an annual allotment of wine that they could secure from their rabbis for religious purposes, but the American rabbinate’s lax regulations for entry allowed new rabbis to become established, whose sole intent was distributing alcohol. The number of rabbis and the size of congregations soared during Prohibition. Davis expands on this idea by quoting Lincoln Andrews, the assistant secretary of the Bureau of Prohibition, who in 1926 stated, “Anybody can become a rabbi… and the bootlegger has taken advantage of it.”

Many American Jews were outraged with this practice, thinking it reflected badly on their community and would make it more difficult to assimilate into American culture. However, some thought bootlegging was the most American activity they could participate in. The gangster glitz and glamour were idolized. The following men were particularly successful; meet America’s most infamous Jewish bootleggers:

Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky was one of the most notorious bootleggers in the United States. Early in his career, he founded the Bugs and Meyer Gang with his childhood friend Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. Lansky worked closely with Charlie “Lucky” Luciano and together they formed the National Crime Syndicate, the powerful interethnic bootlegging network. The Syndicate included several prominent Jewish bootleggers, Moe Dalitz and Abner “Longie” Zwillman. Lansky was known as ‘The Mob’s Accountant’ for his role managing the Syndicate’s finances. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Lansky found success in another recently legalized business: gambling. In 1970, Lansky was indicted on federal tax evasion and fled to Israel, planning to escape under the country’s Law of Return, but he was denied entry due to his criminal status. When Lansky returned to the United States, he was arrested, tried and eventually acquitted.

Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein was a powerful bootlegger, gambler and narcotics dealer, but his greatest feat was fixing the 1919 World Series. In Leo Katcher’s book, “The Big Bankroll: The Life and Times of Arnold Rothstein,” Rothstein is described as “the J. P. Morgan of the underworld; its banker and master of strategy.” He was a millionaire who evaded the law by bribing police and politicians.

Rothstein is an iconic gangster, inspiring fictional characters like Nathan Detroit in the musical “Guys and Dolls,” and Meyer Wolfsheim in the classic novel “The Great Gatsby.” Rothstein’s entire life was gambling, and that’s how it ended. In 1928, Rothstein was murdered at a poker table in Manhattan.

Moe Dalitz

Moe Dalitz began his bootlegging career in Detroit, Michigan, a major port for running and distributing alcohol from Canada. Dalitz hired the violent, predominantly Jewish Purple Gang to protect the alcohol he imported. According to the Detroit Historical Society, “the gang was so ferocious that infamous gangster Al Capone chose to use the gang to smuggle his alcohol into the country.” A majority of the nation’s illegal alcohol came through Detroit, so much that by 1929, illegal alcohol was Michigan’s second leading industry behind automobiles. The Jews’ involvement in the Detroit alcohol industry was well known; Lake Erie was even nicknamed the “Jewish Lake.” In 1937, Dalitz received his sole indictment for bootlegging, a charge that was ultimately dropped.

Abner “Longie” Zwillman

At the peak of his career, Abner “Longie” Zwillman was the head of all major criminal activity in the state of New Jersey. In addition to illegally selling alcohol, he also controlled slot machines, cigarette vending machines and several restaurants. Early on, Zwillman owned motor boats and met rum runners out at sea. He trafficked “as much as 50 truckloads of liquor a night into the Newark port,” according to an FBI report.

In 1923, Zwillman became well known in the racketeering community after shooting the man who controlled “Bootlegger’s Row” in Newark. He continued to gain prominence and soon controlled Newark’s Third Ward. With this power, he helped his preferred candidates win, enlisting Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky to literally kill off the competition.

In the 1950s, there was a federal investigation into Zwillman’s finances; he was ultimately charged with tax evasion. The defense admitted that Zwillman had been a bootlegger during Prohibition, accumulating great wealth, but argued that the statute of limitations had expired on that money. The jury reported it was deadlocked and could not reach a verdict. Zwillman was free.

Bronfman Family

The Bronfman family of Canada, founders of the Seagrams empire, was the most powerful Jewish family during Prohibition. Ironically, Bronfman means “liquor man” in Yiddish. In 1919, when the Volstead Act passed, brothers Sam and Harry Bronfman opened export houses along Canada’s border with North Dakota. According to Peter Newman’s book, “The Bronfman Dynasty; the Rothschilds of the New World,” they bottled the legal minimum of distilled alcohol, mixing it with water, caramel and sulphuric acid. The caramel helped achieve the whiskey color and the acid reacted with the oak barrel to create an aged taste. Sam made millions importing alcohol to the United States. He cut distribution deals with Meyer Lansky and Arnold Rothstein. Al Capone ran Bronfman booze across the Midwest, and the Bugs Meyers Gang protected Bronfman liquor shipments across the border against hijackers. Marni Davis captures Bronfman’s scale of operation in her book, “Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition.”

Sam purchased a Kentucky distillery, dismantled it, sent the pieces north, reassembled it at home, and distilled his own whiskey. He also built an underground pipeline to pump alcohol into the United States. Sam’s involvement in this illicit industry was far-reaching, but his legacy is remembered as a leader in the Canadian Zionist movement.

Abe Rosenberg

The history of Jewish bootleggers is complex and colorful, but for me it’s also personal. A lesser known bootlegger, Abe Rosenberg, who was a luminary in the Scotch whiskey market also happened to be married to my great-grandmother’s first cousin. Unlike the majority of bootleggers who transitioned to gambling, with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Rosenberg applied for and received one of the first wholesale liquor licenses in New York. He legally imported thousands of bottles of single malt Scotch, popularizing this sophisticated spirit and ultimately spurring today’s booming whiskey market. According to whiskey specialists VCL Vintners, when Rosenberg passed away in 1994 he left behind an “incredibly impressive collection of approximately 4,000 casks of the best single malts produced in Scotland over the past 100 years.”

Jewish bootleggers were important players during Prohibition, but their contributions are relatively unknown. Perhaps that is because these “contributions” were illegal and not the most honorable chapter in Jewish American history. I understand; when I learned of my family’s connection to Abe Rosenberg, I was surprised. But alcohol is how Rosenberg survived while supporting his family, becoming a philanthropist, and greatly contributing to the Scotch market that exists today.

There are few Jews who remain as titans in the U.S. alcohol industry. I.W. Harper, a whiskey founded by Isaac Wolfe Bernheim pre-Prohibition, can still be purchased today, as can Elijah Craig Bourbon and Evan Williams Bourbon, which are produced by Heaven Hill distillery, founded by the Shapira family post-Prohibition. More recently, in 2011, the Jewish Whisky Company was started as a bottler of kosher single-cask whiskeys. While Jewish bootleggers are often overlooked, they are icons of Prohibition and their involvement continues a tradition of producing and selling alcohol, albeit illegally, that is still continued today.