If you made a list of the most Jewish foods, it would likely include dishes like chicken soup, hamin, gefilte fish and challah. But what about chocolate? Probably not.

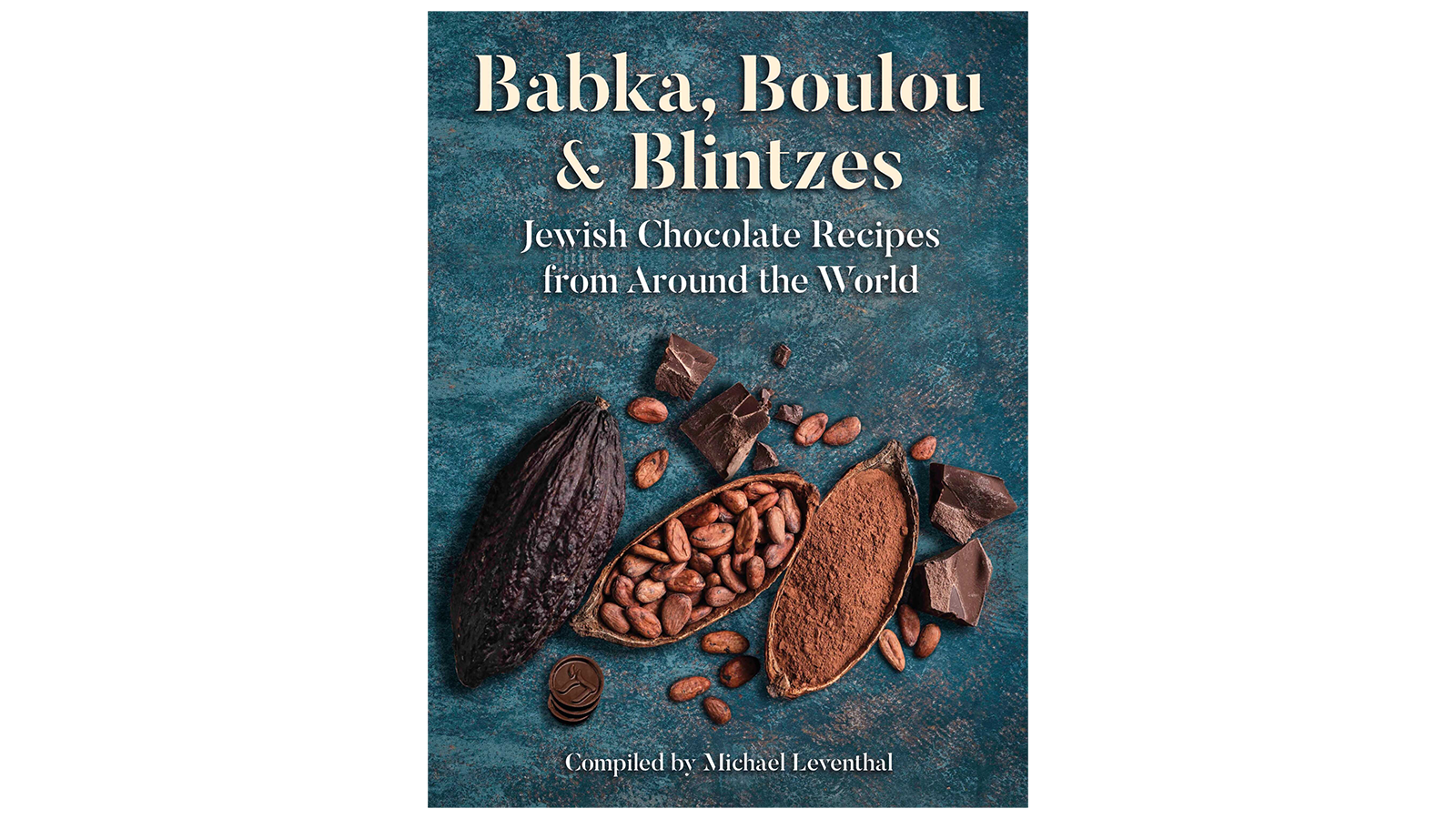

If it were up to Michael Leventhal, author of “Babka, Boulou and Blintzes: Jewish Chocolate Recipes from Around the World”, chocolate should be right up there with those iconic Jewish foods. That’s because, Jews have played a critical role in its production and popularization.

According to Leventhal, Spanish merchants who were Jews or had Jewish backgrounds (conversos who were forced to convert during the Inquisition in Spain) were integrally involved in importing and selling cocoa beans. They eventually learned to make chocolate from those beans. As the Jewish diaspora spread out from Spain following the Inquisition, so, too, did their chocolate-manufacturing know-how.

Leventhal became interested in the Jewish role of chocolate after reading Rabbi Deborah Prinz’s book, “On the Chocolate Trail.” He describes himself as an “unrepentant chocoholic” so it was a wonderful revelation to him that Jews were so involved in the marketing and manufacturing of the stuff.

The Nosher celebrates the traditions and recipes that have brought Jews together for centuries. Donate today to keep The Nosher's stories and recipes accessible to all.

Nearly three years ago he took his family to Bayonne, a city in southern France near the border with Spain, to dive deeper into the historical connection between Jews and chocolate production. Bayonne is known as France’s chocolate capital, and the two chocolate museums there credit the Jews’ role in Bayonne’s chocolate industry. In the 17th century Bayonne, the Jews lived in a district called Saint Esprit. By day, they lugged their heavy, cocoa-grinding equipment into the center of town; by nightfall, they had to bring it back with them to their homes in the ghetto.

Jewish bakers introduced chocolate cakes and fillings to their neighbors, but both elight and resentment grew. The Bayonnais, according to Leventhal, “fought to ban Jews from making chocolate — once they had learned the craft themselves.” By the 1720s, there was “a series of laws…forbidding Jews to make chocolate in shops and warehouses in Bayonne.” By 1860, he continues, “there were only two Jewish artisans left in Saint Esprit practicing chocolate-making, but in Bayonne there were still 32 chocolate-makers — a very large number for a fairly small town.”

In addition to detailing Bayonne’s chocolate history, Leventhal shows how chocolate manufacture spread throughout Europe and North America, often thanks to Jewish entrepreneurs. In 1650, Jacob the Jew opened England’s first coffee house where he served coffee and hot chocolate. A few years later, a Jewish chocolatier began making chocolate in Belgium. And so the Jewish chocolate trail meanders.

After Leventhal’s introductory essays about the history of chocolate and Jews’ role in popularizing it, you can dive into the 53 recipes Leventhal aggregated from important Jewish food writers. The collection includes dishes that use chocolate in both sweet and savory ways.

The oldest entry comes from the mother of all Jewish food writers, Joan Nathan. It is a 400-year-old chocolate almond cake recipe passed orally from mother to daughter — first in Spanish, then in Ladino and finally in French — from a Jewish family from Bayonne.

You can find here a recipe for hot chocolate from Curaçao, the Caribbean Island where a Jew from Bayonne settled in the late 16th century, and helped establish a chocolate industry there. Old recipes are joined by new ones, some that have never before been published, like Rachel Davies’ chocolate tahini bark or Amir Batito’s Cream Cheese and Nutella Blintzes.

In assembling the recipes, Leventhal tried to get a representative sampling from around the world, including Curaçao, Israel, Egypt, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, the United States and Turkey. From Tunisia, there is a recipe for boulou, described as a cross between a cake and a biscuit. From Australia’s Monday Morning Cooking Club, there is a recipe for a chocolate and marmalade celebration cake. For a savory recipe there is an even a classic eggplant caponata from Sicily made with, yes, chocolate.

The book, says Leventhal, was his “lockdown project.” After his family trip to Bayonne, he began gathering chocolate recipes for himself. He decided to write this book and use it as a fundraising vehicle for Chai Cancer Care, a British organization that supports cancer patients in a myriad of ways. The profits from the sale of this book go directly to Chai.

This book offers so much: Jewish history, delicious recipes from shining lights in the culinary world and, and in buying it you can feel good that you are doing good by supporting Chai Cancer Care. Even chocolate can’t be sweeter than all that.