In 2008, Sylvie Bigar, a food and travel writer based in New York City, approached her editor at (the now closed) Food Arts Magazine with a story idea. Bigar was intrigued by one-pot dishes in general, and by one in particular: cassoulet, an ancestral bean and meat dish from Occitanie in Southern France. She’d never tried it but heard that “it tastes like velvet cocoa” and that it was the object of all types of mysterious traditions. Her editor urged her to go to the stew’s source and find out more.

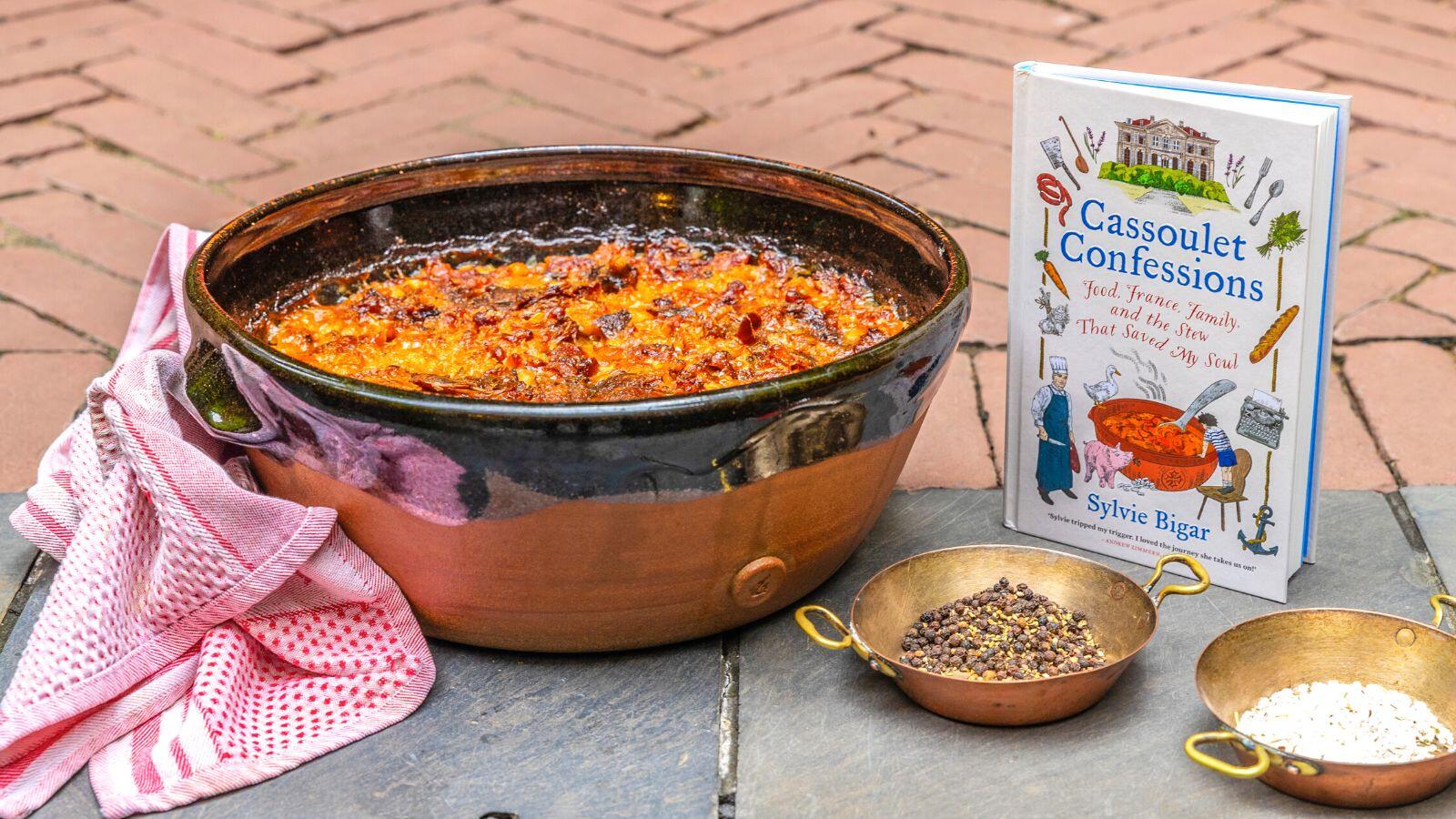

Bigar decided to travel to the medieval city of Carcassonne, in Occitanie, to interview locals, learn how the dish was made, write a piece about its history, and call it a day. But things don’t always work out as planned. That one article turned into a 10-year journey into food, history, family and religion, culminating in her new book, “Cassoulet Confessions: Food, France, Family, and the Stew that Saved my Soul.”

Shortly after her arrival in Carcassonne in April 2008, Bigar met with the local master of cassoulet, Eric Garcia, the co-founder of the Académie Universelle du Cassoulet, at his restaurant Domaine Balthazar. There, she had her first bite of the rich stew made of creamy white beans, pork rind, pork belly and duck confit, served by people in “scarlet robes with billowy sleeves” singing a song in a mysterious language that she later learned was Occitan, the medieval romance language indigenous to Southern France. To her shock, the stew tasted, she writes in the book, “of home.”

This made no sense.

The Nosher celebrates the traditions and recipes that have brought Jews together for centuries. Donate today to keep The Nosher's stories and recipes accessible to all.

In Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past,” the narrator takes a bite of a buttery madeleine cake and is transported back to his childhood. But Bigar, who was raised in Geneva, Switzerland, the youngest of four daughters to Jewish parents, never ate cassoulet growing up. While her family’s culinary Jewish traditions were limited to charlotte aux pommes (apple bread pudding) for Rosh Hashanah and matzah topped with rich salted butter and honey on Passover, they drew the line at pork-heavy cassoulet. So why did that first bite feel so familiar?

Not long after she first tasted the fat-studded, slow-cooked stew, Bigar met Chef Garcia’s wife, who told her that cassoulet kept the Garcia family together. Bigar wondered what kept her family together. The question preyed on her mind, prompting her to explore her family’s story in tandem with her immersion into the evocative cassoulet.

Throughout the course of the book, Bigar moves between the past and present — going back generations to her great-grandfather, a rabbi in Alsace in northeastern France, and to her agnostic Swiss grandparents who hoped their Swiss citizenship would save them from the Nazis. She wonders about her heritage, theorizing that perhaps her ancestors arrived in France from Spain.

“Had they stopped in the southwest of France on their way to Alsace? Had they savored cassoulet? Were there, in fact, ancestral beans running through my veins?” Bigar writes. Could that explain her instinctive connection to this dish?

Seminal Jewish food historians and writers, such as Gil Marks (“Encyclopedia of Jewish Food”) and Claudia Roden (“The Book of Jewish Food”) offer another explanation. They believe there is a strong connection between cassoulet and cholent, a bean and meat Shabbat stew.

“Although the French are loath to admit it, the classic Southern French dish cassoulet is most certainly a descendant of the Jewish schalet,” (the term used for cholent in parts of France and Germany) writes Marks.

Not everyone agrees. Joel Haber, a food historian who is currently writing a book about Shabbat stews, argues that cassoulet and cholent are, at best, cousins. There may have been parallel development between the two, but his research has not found a direct connection.

Be that as it may, the power of cassoulet — the taste, tradition and community that grew up around the eating and making of it — sparked a journey that led Bigar to a greater understanding of herself and of her family.

In the final part of her memoir, Bigar includes several recipes for cassoulet, including a take on Eric Garcia’s, redolent of garlic, pork sausage and fresh pork rind. The pig skin and gelatin give a richness to the stew and help to form the crust, writes Bigar.

“Although I have not tried it, I think that if you take veal shank or veal hock or knuckle, you could get the same gelatin and make a kosher cassoulet,” she told The Nosher.

Bigar reserves one of the book’s six recipes for cholent. Unlike classic cassoulet — and the rest of the recipes — it is pork free. Bigar’s cholent is an evolved version of this slow-cooked Shabbat dish, sweetened with allspice, honey, chestnuts and butternut squash. As Marion Sultan, Bigar’s friend and recipe tester, is originally from Tunisia, it isn’t a surprise that the recipe incorporates elements of the Sephardic answer to cholent, hamin.

Could this indicate that, after 10 years digging into the ways of cassoulet, Bigar now plans to study the history of cholent?

“It’s time to move on,” she told The Nosher. “But I do plan to visit Colmar, in Alsace, France, where my great-grandfather was from. And who knows what will happen then.”